Abstract

In the whole history of hemophilia, it is generally accepted that the main development in understanding the cause and the inheritance type of the disease accomplished in the last century.But, who really was the first to describe the disease?

The priority of the disease is still a matter of argument. We followed the tracks of hemophilia in history since the ancient times to the recent, trying to identify the priority in each discovery related to the disease, chasing the advances in treatment.

We found that the Arabian physician Albucasis may be the first who described the disease. He defined the disease, witnessed some cases, named it, and even suggested a treatment. Then, more than seven centuries had passed until the concern about the disease revived, thanks to its spread in the royal families of Europe.

In our treatise, we tried to shed light on the most important events in the history of hemophilia. We clarified how hemophilia spread in the royal families through Europe. Finally, we mentioned the discoveries and inventions in the recent age.

Introduction

The history of haemophilia represents one of the human mind’s attempts to define and encompass a mysterious fascinating phenomenon. Although some western historians claimed the priority of discovering this phenomenon to Jewish writings or recent physicians, the real priority may be attributed to Albucasis, the Arabian physician who died in the 11th century. Treatment options for hemophilia patients present one of the most stimulating treatment stories of any patient group with an inherited disorder.

Definition:

Haemophilia is derived from the Greek “haima” which means blood and “philia” which means friend.In Arabic language; haemophilia means Naaor (ناعور) which means the unstopped bleeding vessel.

Haemophilia (also spelled Hemophilia in North America) is conventionally a group of hereditary genetic disorders that impair the body’s ability to control blood clotting or coagulation. Thus, prolonged bleeding and re-bleeding are the diagnostic symptoms of haemophilia, especially haemarthrosis, haematuria and large bruises. The most common form of haemophilia is haemophilia A which is anX-linked recessive inherited bleeding disorder resulting from a mutation in the F8Cgene which results ina deficiency of factor VIII. About a third of mutations are new sporadic mutations. Whereas, haemophilia Bis an X-linked recessive inherited bleeding disorder, previously known as Christmas disease, resulting from a mutation in the F9gene which causes a deficiency of factor IX. Similarly to most recessive sex-linked, X chromosome disorders, only males typically exhibit symptoms. Because females have two X chromosomes and because haemophilia is rare, the chance of a female having two defective copies of the gene is very low, thus females are almost exclusively asymptomatic carriers of the disorder. Bleeding manifestation in hemophiliac individuals are related to the level of reduced factor. There are other rare forms of haemophilia, which are less important.

Hemophilia in the Ancient and Medieval Ages:

The genetic mutation originally responsible for haemophilia in mammals is generally considered to be many thousands of years old.

The study of blood coagulation can be traced back to about 400 BC and the father of medicine, Hippocrates. He observed that the blood of a wounded soldier congealed as it cooled. Additionally, he noticed that bleeding from a small wound stopped as skin covered the blood. If the skin was removed, bleeding started again.

Aristotle noted that blood cooled when removed from the body and that cooled blood initiated decay resulting in the congealing of the blood.

According to many European historians, the earliest assumed written references to what may have been human haemophilia are attributed to Jewish writings of the 2nd century AD. A ruling of Rabbi Judah the Patriarch exempts a woman’s third son from being circumcised if his two elder brothers had died of bleeding after circumcision. Additionally, Rabbi Simon ben Gamaliel forbade a boy to be circumcised because the sons of his mother’s three elder sisters had died after circumcision.

Anyway, the Jewish writings didn’t consider this condition as a disease. They included no medical description of the disease, nor treatment. Besides, death after circumcision may result from any other accompanying reasons like infections. As a result, those writings are considered as an observation of a condition may relate to haemophilia, but may not.

In the 12th century, Maimonides (1135-1204 AD)applied the rabbinic ruling to the sons of a woman who was twice married.

Albucasis, the First Physician Who Described Hemophilia:

The famous physician Al-Zahrawi – Albucasis (936-1013 AD), in the second Essay of his medical encyclopedia “Kitab al-Tasrif”, described a disease which he named “علة الدم” or blood disease. His description corresponds with haemophilia.

Albucasis was far ahead in his description for many reasons: firstly, his naming was indicative of the real cause of the disease.

Secondly, he noticed the spread of the illness in just one village, which is attributed to the inherited nature of it.

Thirdly, he was the first who noticed and described the disease, because, as he said, he didn’t read of it in any of the ancient’s medical books. Actually, we tried to find a former description of the disease in some ancient physicians, but we found nothing.

Fourthly, he noticed the limitation of the disease to males and their boys.

Fifthly, he characterized the disease with easy bleeding after minor traumas which is nowadays considered the primal symptom of the disease. He mentioned examples of three who boys bled until they died.

Sixthly, he admitted that he didn’t know the cause of the disease which was impossible to be discovered in his time. Albucasis didn’t pretend that he knew the cause which indicates his scientific method.

Finally, he recommended using the cauterization of the bleeding place until the vessels stop bleeding.

The treatment he suggested represents the most beneficial remedy available in his time.

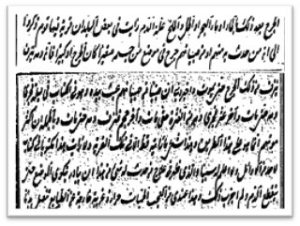

From the Manuscript of Albucasis’s book “Kitab Al-Tasrif” describing “Blood Disease” or Hemophilia

Hemophilia in the Recent Age:

Down the years there were rare scattered records of bleeding disorders more or less closely agreeing with the clinical picture we know. In 1770, William Hewson challenged the cooling theory and believed that air and lack of motion were important in the initiation of clotting. Hewson described the clotting process, demonstrating that the clot comes from the liquid portion of blood, the coagulablelymph, and not from the cells, disproving the cooling theory.

The first recent descriptions of haemophilia are from the end of the 18th century. In 1803, Dr. John Conrad Otto (1774-1844), an American physician, published an account about “a hemorrhagic disposition existing in certain families “in the “New York Medical Repository”. He recognized that the disorder was hereditary and that although it affected only males the disorder was transmitted by unaffected females to a proportion of their sons. He was able to trace the disease back to a woman who settled near Plymouth, New Hampshire in 1720 AD. These accounts began to define a clinical syndrome on which the 19th century developed an extensive literature.

The recent and rather strange name ‘haemophilia’ which means ‘love of blood’ appeared in the title of Hopff’s treatise of 1828 published at the University of Zurich. Numerous dissertations, treatises and many papers were published in journals in the following years.

The rare occurrence of true haemophilia in the female is supposed first to have been described by Sir Frederick Treves in 1886, from a first-cousin Marriage.

The involvement of joints, to us the most characteristic symptom of haemophilia, was described in detail by Konig only in 1890.

The Royal Hemophilia:

Haemophilia figured prominently in the history of European royalty in the 19th and 20th centuries. Queen Victoria, through two of her five daughters (Princess Alice and Princess Beatrice), passed the mutation to various royal houses across the continent, including the royal families of Spain, Germany and Russia. Victoria’s son Leopold suffered from the disease. For this reason, haemophilia was once popularly called “the royal disease”.

The spread of hemophilia in the royal families of Europe was a very important factor in the development of medical knowledge about the disease. The physicians dived into the cases of hemophilia, trying to uncover its secrets, looking for the suitable remedy to enjoy the favor of the royal families.

The condition is not known among any of the Queen’s antecedents, so that it is supposed that a mutation occurred at spermatogenesis in her father Edward, Duke of Kent, a mischance perhaps made more likely by the fact that he was in his fifties when she was conceived.

Haemophilia in the British Royalty:

Leopold was severely affected and suffered numerous bleeding episodes. In 1868 the British Medical Journal noted a ‘severe accidental haemorrhage’ leading to ‘extreme and dangerous exhaustion by the loss of blood’ at the age of 15. In 1884 he died of a cerebral haemorrhage after falling and hitting his head. He was 31 years old. His daughter, Alice, born the previous year (1883 AD), who became Princess of Teck, had a haemophilic son, Rupert, Viscount Trematon, born in 1907, who died at 21, also of a cerebral heamorrhage. The present British Royal Family haven’t inherited haemophilia.

Haemophilia in the German and Russian Royalty:

Alice, Victoria’s third child, passed it on to at least three of her children: Prince Friedrich, Princess Irene, Princess Alix and Princess Victoria.

Prince Friedrich Died before his third birthday of cerebral bleeding resulting from a fall.

Princess Irene of Hesse and by Rhine (later Princess Heinrich of Prussia), who passed it on to two of her three sons: Prince Waldemar of Prussia. Survived to age 56; had no issue. Prince Heinrich of Prussia whodied at age 4.

Princess Alix of Hesse and by Rhine. Alix married Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, and passed it on to her only son, Tsarevitch Alexei who was murdered by the Bolsheviks at the age of 13. Alexei’s haemophilia was one of the factors contributing to the collapse of Imperial Russia during the Russian Revolution of 1917. The illness of the Tsarevich cast its shadow over the whole of the concluding period of Tsar Nicholas II’s reign and alone can explain it. Without appearing to be, it was one of the main causes of his fall, for it made possible the phenomenon of Rasputin (1869-1016) and resulted in the fatal isolation of the sovereigns who lived in a world apart and wholly absorbed in a tragic anxiety which had to be concealed from all eyes. Rasputin used hypnosis to relieve pain and/or slow hemorrhages, and sent away doctors who some claim were actually prescribing then “wonder drug” aspirin. It is not known whether any of Alexei’s sisters were carriers, as all four were executed with him before any of them had issue. One, Grand Duchess Maria, is thought by some to have been a symptomatic carrier, because she hemorrhaged during a tonsillectomy.

Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine, Alice’s oldest child and maternal grandmother to Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, might have inherited the mutation, though the gene remained hidden for several generations before reappearing in the descendants of her eldest granddaughter, Princess Margarita of Greece and Denmark.

Haemophilia in the Spanish Royalty:

Princess Beatrice, Victoria’s ninth and last child, passed it on to at least two, if not three, of her children: Princess Victoria Eugenie, Prince Leopold and Prince Maurice.

Princess Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg (later Queen Victoria Eugenia of Spain), who passed it on to Infante Alfonso and Infante Gonzalo. Infante Alfonso of Spain, Prince of Asturias who died at age 31, bleeding to death after a car accident whereas Infante Gonzalo who died at age 19, bleeding to death after a car accident. Prince Leopold of Battenberg. Later Lord Leopold Mountbatten. Died at age 32 during a knee operation.

Prince Maurice of Battenberg whokilled in action in World War I in 1914 at the age of 23. Maurice’s haemophilia is disputed by various sources. It seems unlikely that a known haemophiliac would be allowed to serve in combat.

Queen Victoria and her family. Victoria (circled lower right) transmitted the gene to her son Leopold (circled) and to two daughters, one of whom, Princess Beatrice, is depicted (upper right). Tsarevitch Alexei (below) was Victoria’s great-grandson.

Hemophilia in the Last Century:

It was Paul Oskar Morawitz (1879-1936) in 1905 who assembled coagulation factors into the scheme of coagulation and demonstrated that in the presence of calcium (Factor IV) and tissue thromboplastin (Factor III), prothrombin (Factor II) was converted to thrombin, which in turn converted fibrinogen (Factor I) into a fibrin clot. He introduced his landmark theory in Ergebn Physiol magazine. This theory persisted for 40 years until Paul Owren, in 1944, discovered a bleeding patient who defied the four-factor concept of clotting. Owren observed a cofactor that was involved in the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin. Thus factor V was discovered.

Many reputable scientists claimed early success in treating with unusual substances. A report in The Lancet in 1936 extolled the virtues of a bromide extract of egg white. As recently as 1966, a report in the esteemed scientific journal Nature claimed that peanut flour was also effective for the treatment of hemophilia. The first hint of success came with the report from R.G. Macfarlane in 1934 that snake venoms could accelerate the clotting of haemophilic blood, and he reported success in controlling superficial bleeds in people with hemophilia after topical application.

Factor VIII was discovered in 1937 by American researchers A.J. Patek and F.H.L. Taylor. They found that intravenous administration of plasma precipitates shortens blood clotting time. Taylor later calls the precipitates anti-hemophilic globulin.In 1939, American pathologist Kenneth Brinkhous showed that people with hemophilia have a deficiency in the plasma factor he later called anti-hemophilic factor. In 1952, Loeliger named this factor VII.

Buenos Aires physician Pavlovsky reported that the blood from some hemophiliac patients corrected the abnormal clotting time in others. In 1952, Rosemary Biggs from Oxford U.K. calls it Christmas disease, named for the first patient, Stephen Christmas. The clotting factor was called Christmas factor or factor IX.

Factor XI deficiency was described in 1953 as a milder bleeding tendency.

In 1955, Ratnoff and Colopy identified a patient, John Hageman, with a factor XII deficiency who died from a thrombotic stroke, not a bleeding disease.

Factor X deficiency was described in 1957 in a woman named Prower and a man named Stuart.

In 1960, Duckert described patients who had a bleeding disorder and characteristic delayed wound healing. This fibrin stabilizing factor was called factor XIII.

In the early days, treatment of hemophilia A patients consisted of giving whole blood units to relieve symptoms. Not until 1957 was it realized that the deficient coagulation protein was a component of the plasma portion of blood.

In 1958,Inga Marie Nilsson, a Swedish physician, begins prophylaxis in treatment of boys with severe hemophilia A. Regular prophylactic treatment does not begin until the early 1970s.

The World Federation of Haemophilia was established in 1963. Cryoprecipitate, a plasma derivative, was discovered by Dr. Judith Poolin 1964. This product is produced as an insoluble precipitate that results when a unit of fresh frozen plasma is thawed in a standard blood bank refrigerator. Cryoprecipitate contains fibrinogen, factor VIII, and vWF. This product is extracted from plasma and usually pooled before it is given to the patient according to weight and level of factor VIII. This product presented a major breakthrough for the hemophilia population because it was an easily transferable product affording the maximum level of factor to the individual.

Next in the chronology of treatment products for hemophilia was clotting factor products. These freeze-dried products were developed in the early 1970s. The products were lyophilized and freeze-dried and could be reconstituted and infused at home. This treatment offered the hemophilia population an independence that they had never previously experienced. Finally they were in control because they could self-infuse when necessary and provide themselves with prompt care when a bleeding episode developed.

Another landmark was the recognition by Italian Prof. Pier Mannucci in 1977 that desmopressin (DDAVP) could boost levels of both factor VIII and von Willebrand factor, and this remains a useful option in mild forms of these conditions.

But adark cloud loomed over the bleeding community. Approximately 80% to 90% of hemophilia A patients treated with factor concentrates in the period 1979-1985 became infected with the HIV virus. Factor concentrates were made from pooled plasma from a donor pool that was less than adequately screened. Additionally, manufacturing companies were less than stringent with sterilization methods and screening for HIV virus did not occur in blood banks until 1985. When each of these factors is brought to bear, the tragedy to the bleeding community is easily understood.

According to the National Hemophilia Foundation, there are 17,000 to 18,000 hemophilia patients (hemophilia A and B) in the United States. Of those, 4200 in the United States and about 1200 in the UK are infected with HIV/AIDS. There are no numbers available for wives or children who could have been secondarily infected.

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) was first identified in 1989, and it soon became clear that an even higher proportion of people with hemophilia had been exposed to this virus. Fortunately, the introduction of physical treatments of concentrates such as exposure to heat or the addition of a solvent-detergent mixture has effectively eliminated the risk of the transmission of these viruses. The structure of the factor VIII gene was characterized and cloned in 1984. This led to the availability of recombinant factor VIII. Recombinant products became available in 1989 and represent the highest purity product because they are not human derived. Recombinant technology uses genetic engineering toinsert a clone of the factor VIII gene into mammalian cells, which express the gene characteristic. Production expenses for this product are unfortunately the most costly, and these costs are passed on to potential users. Most individuals with hemophilia in the United States use factor concentrates prophylactically.10Life expectancy of a child growing up with haemophilia today is comparable to that of someone without a bleeding disorder. In 1998,Gene therapy trials on humans began. In the future, gene therapy is considered a realistic goal.

Conclusion:

To sum up, it’s widely clear that the main improvements in understanding the cause and the inheritance type of hemophilia, and the major advances in its treatment was actually done in the last hundred years. In spite of this fact, historians of medicine couldn’t deny that Albucasis (Al-Zahrawi) was the first who noticed the disease. We need to reconsider this fact when we try to rewrite the history of hemophilia.

References

Books and Essays:

- ABU’L-QASIM ALZAHRAWI, 1986- Kitab al-Tasrif I. Edited byFuatSezgin, Publications of The institute for the history of Arabic-Islamic science, Frankfurt-Germany. Reproduced from MS 502 Suleymaniye Library Istanbul 293 paper.

- ABU’L-QASIM ALZAHRAWI, 2004- Kitab al-Tasrif. Edited by Sobhi Mahmoud Hemmami, 1st edition, AlKuwait foundation for scientific progress, Kuwait, 1377 pages.

- BAIN B. J.,and GUPTAR.,2003-A–Z of Haematology. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Massachusetts-USA; 233 Pages.

- , 2007- Hematology in Practice. F. A. Davis Company, Philadelphia-USA; 348 Pages.

- INGRAM G. I. , 1976- The history of haemophilia, clin. Path, 1976 June; 29(6): 469–479.

- OFOSU F.A., FREEDMAN J., Semple JW. Plasma-Derived Biological Medicines Used to Promote Haemostasis.ThrombHaemost. 2008 May; 99(5):851-62.

- POHLE F. J. and TAYLOR F. H. L.The Coagulation Defect in Hemophilia. The Effect in Hemophilia of Intramuscular Administration. of a Globulin Substance Derived from Normal Human Plasma. J Clin Invest.1937 September; 16(5): 741–747.

- PROVAN D., 2003-ABC of Clinical Haematology, BMJ Books, London-UK; 75 pages.

- RUHRÄH J. John Conrad Otto (1774-1844), A Note on The History of Hemophilia. J Dis Child.1934;47(6):1335-1338.

- SCOTT M. G., GRONOWSKI A. M., EBY C. S., 2007- Tietz’s Applied Laboratory Medicine. 2nd Edition, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New Jersey-USA. 679 pages.

Web Sites:

- http://www.buzzle.com/articles/history-of-hemophilia-disease/

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grigori_Rasputin

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haemophilia

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haemophilia_in_European_royalty

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Morawitz

- http://famousamericans.net/johnconradotto/

- http://www.haemophiliacare.co.uk/general/history_haemophilia.html

- http://www.haemophiliacare.co.uk/general/hiv_hep_c.html

- http://www.haemophiliacare.co.uk/general/past_future.html

- http://www.haemophiliacare.co.uk/general/history_hepatitis.html

- http://www.hemophilia.org/NHFWeb/MainPgs/MainNHF.aspx?menuid=178&contentid=6&rptname=bleeding

- http://www.wfh.org/2/1/1_1_3_HistoryHemophilia.htm

- http://www.wfh.org/2/1/1_1_3_Link1_Timeline.htm